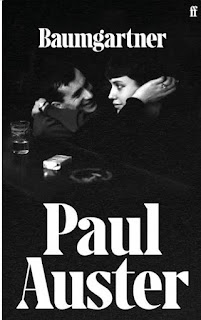

Baumgartner

After the epic nature of 4321 (900 + pages) Baumgartner is a light work, yet still with Auster’s characteristic depth of thought and playfulness with fictional form.

We open with a writer at his desk, ‘pen in hand … midway through a

sentence in the third chapter of his monograph on Kierkegaard’s pseudonyms’ (p.

1). A New Yor intellectual, in other words – but one distracted by something

burning on the stove downstairs; the call of UPS (Baumgartner orders books to

have a moment of Molly’s company); and a young visitor whose father has severed

off some fingers and so Rosita has come instead of her mother, his cleaner (how

Auster). As the reviewers in The Guardian and The New York Times note, the novel begins at pace. Soon

Baumgartner has fallen down a staircase in his basement, and has been rescued by a

young man on his first day in the Public Service Electric & Gas Company.

Chapter 2 introduces

a metaphorical idea about phantom limbs and how this might help Baumgartner to

understand his decade-long grief for his wife’s tragic death (‘He is a human

stump now, a half man who has lost the half of himself that had made him whole

…’ [p. 28]’). In exploring this grief, Baumgartner comes across a passage of

his wife’s writing about her own loss – that of her first love, Frankie Boyle. Frankie,

athlete, and soulmate, comes to life in a thirteen-page interlude from the main

narrative. This leads Baumgartner to recall his first stages of grief, which

included him typing ‘gibberish’ on Anna’s typewriter because he missed her old

sounds, and later, his exploration and publication of her poetry. Another

extract from Anna’s diary (ten pages) interrupts the narrative again in Chapter

3 and then we have the story of their early love and marriage, before we jump

forward to his current love, Judith, the product of a ‘well-heeled Jewish

family from the New York suburbs’ (p. 91). Other interludes (criticized by the Guardian

reviewer) include a passage ‘written’ by Baumgartner in which he describes a

visit to Ukraine in September 2017 where he comes to understand something of

the name Auster and the horror of war and the Holocaust.

So, as the

novel progresses, Baumgartner is at work on ‘Mysteries of the Wheel’, while he

prepares to host a young academic who has become interested in his deceased

wife’s poetry and sets out on a fateful journey to meet her on January 3, 2020.

Baumgartner drives a Subaru, normally a reliable car, but the expectation of

plot described by Fiona Maazel (New York Times reviewer) finally catches

up with our protagonist in the dying pages of the novel (so to speak).

What to

make of all of this? I am a one-eyed Paul Auster fan, so while I don’t think it

is his best work, I was happy to go along for the short ride (202 pages). It’s

true that there are stories here that open and aren’t fully developed – and

perhaps the novel might have opened further in another 202 pages. The art might be in reading the novel as the character’s memoir: clock ticking down,

not as old as he might be in his mind, living in the past and yet finishing two

books, even if the last one turns out to be (as he thinks) ‘bullshit on toast’

(p. 191). Auster’s novel isn’t that – and one imagines – neither is

Baumgartner’s.

(This

review was written before the sad news of Auster’s death on 30 April 2024. Here’s

the New

York Times article celebrating this wonderful writer, truly one of the greats).

Comments

Post a Comment