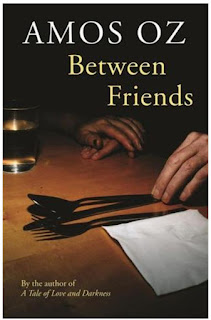

Between Friends

I bought the hardback of Amos Oz's Between Friends (2012) this year from a good bookstore, on sale for $5. I felt a bit sad buying the book at this price, like a man taking pity on a stray dog at the pound of some undoubtedly good pedigree, misplaced. And that feeling of melancholy lasted with me as I read the book, the fourth I have read by the Israeli writer, peacemaker, and intellectual. This is a short book so I will tell a little of my other readings first. Black Box (1988) is written as a series of letters between divorcees with shared responsibility for their son, Boaz. Just having a character, Alec, as a university professor, travelling between locations as part of the correspondence introduces a political and social complexity. It’s an intellectual book about emotional issues; something that fills me with envy as a writer. In the Land of Oz (1983; 1993) is a memoir of voices of Israel and the West Bank from the 1980s – of both and all sides (if you can see that paradox