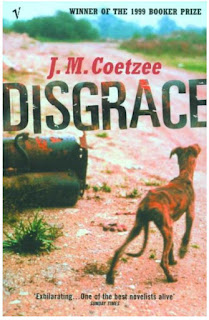

Disgrace

I have had 'Disgrace'

on my shelf for a while now, and at last, I felt ready to engage with it.

Coetzee is a much-revered writer, so the fault is all mine – the only other Coetzee novel I have read is the experimental 'Diary

of a Bad Year' (2007). 'Bad Year' involves

a 72-year-old South African writer who falls for a younger woman. 'Disgrace' begins with a similar premise –

52-year-old Professor David Lurie moves from a falling for a woman whose love

he pays for (Soraya) to an even less appropriate target for his affections: a

student in his Romantic literature class. Melanie is at first rather passive in

the affair, but a menacing boyfriend and a protective, prayerful father put an

end to things and Professor Lurie is in trouble with the university authorities. Were he

willing to make a public apology, the matter might be put behind him;

but he is not and his days of teaching are over.

At this point the novel moves from the diary of a bad man to

a post-Apartheid novel. The connection is the question of what made the professor

feel so entitled to act as a predator, to his downfall as a man who cannot protect his own daughter.

In the end, Lurie can only dream of

redemption in art (he works on an opera about Lord Byron’s final days but ends

up singing only to himself in a compound behind an animal shelter). What fills

Lurie with rage and puzzlement is Lucy’s acceptance of her rape by three men,

whose territory her land inhabits: ‘What if … what if that is the price one

has to pay for staying on … they see me as owing something. They see themselves

as debt collectors, tax collectors’ (p.158). While he cannot understand his

daughter’s decision to stay and to have a child from her rape, Lurie is not without

understanding of his neighbour and the colonial legacy that he represents as a

Professor of English:

‘Lucy is our benefactor,’ says

Petrus; and then, to Lucy: ‘You are our benefactor.’

A distasteful word, it seems to [Lurie], double-edged,

souring the moment. Yet can Petrus be blamed? The language he draws on with

such aplomb is, if only he knew it, tired, friable, eaten from the inside as if

by termites. Only the monosyllables can still be relied on, and not even them

(p.129).

I found this to be an engaging novel of some importance, disturbing in its representation of male privilege (both white, and black) and ultimately for the lack of redemption for Professor Lurie. His apartment is ransacked, and his books and records stolen. He spends ‘money like water’ (p.211) until he is without funds, passing his time as a volunteer assistant in an animal shelter where animals are euthanized rather than cured, where is a ‘dog-man’ without hope for the future, old at 52 – an utter disgrace, without a prodigal’s redemption or a father’s forgiveness.

As for suffering for his art and being reborn that way? He begins his opera on piano with the hope of a triumphant return to society, but ends up writing with the ‘plunk-plunk’ squawk of a banjo in a ‘desolate yard in Africa’ (p.214). Coetzee meanwhile won the Booker Prize for a second time with this sad song, and the Nobel Prize shortly thereafter. Despair and disgrace can be highly prized, but it takes a master of the form to write sentences like this one: ‘His hopes must be more temperate: that somewhere from amidst the welter of sound there will dart up, like a bird, a single authentic note of immortal longing’ (p.214). Oh, to write that note!

Comments

Post a Comment