How to be a Public Author

Paul Ewen is a New Zealand writer who lives in London. His character Francis Plug manages to be both witless and funny at the same time, in the manner of Flight of the Conchords taking on New York with their folk-rock (in this case, Plug is an English gardener and would-be novelist). The Australian Text Publishing edition includes the summation that the book is ‘an affectionate satire on the world of literature’. It is comic, and many of the misadventures are of the more genteel kind, but I am not sure that the satire can be described as ‘affectionate’. In fact, what I liked best about Francis Plug’s How to be a Public Author was the juxtaposition of Plug’s generous eccentricity (albeit in an alcoholic haze) and the intolerance, indifference and meanness of both the middle-class audiences of literary events, and their self-satisfied authors. There are a few exceptions in Plug’s recollections of his visits to book readings, but Ruth Rendell’s “SHOO! SHOO!” (178) cuts to the chase.

The novel purports to be Plug’s memoir of literary events,

and in this sense, non-fiction, though he introduces surreal elements into the

story so that he might qualify for entry into next year’s Booker Prize. The

current year’s Booker Prize evening is the climax of Plug’s current adventures,

which have included various Booker Prize past-winner readings and an extended

section at the Hay Festival, which Plug attempts to capture in a t-shirt line: The Hay Festival is a blank field filled

with words (I, for one, would buy one).

At various points in the readings, Plug wonders about why

the protection of hunting birds outweighs human poverty; how it is that heavy

police protection guard the ‘young tanned bankers in their suits … laughing and

carefree’. He observes ‘fittingly attired gents’ attend the ‘Booker’ and make

‘furtive eye movements’ at Plug’s ignorance when he asks if they are ‘putting

on a JD tonight?’ (282) Class commentary such as this could easily come across

as bitter rantings, so Ewen is careful to make manifest Plug’s foolish

behaviour and social incompetence. Like Chaplin, or Laurel and Hardy, Plug has

a way of re-emerging from beneath the most downtrodden and humiliating circumstances,

while Ewen builds a narrative that gradually reveals Plug’s poverty and

(hidden) despair.

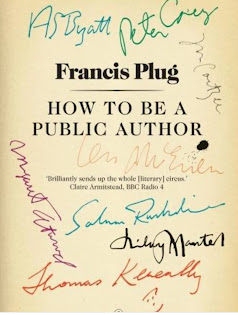

When bookshops are closing, and festivals have turned

genuine authors into literary show ponies, Plug both tries to 'plug' himself, and

'plug a hole' in the sinking ship of literature in the shallow age in which we

now find ourselves. Even the collection of books Plug has signed made me wonder

about the individuality of my reading. Sure, the Booker Prize is a significant

literary achievement and sign of the very highest merit. But have I, too,

fallen victim to the ‘ker-ching eyes’

(285) of publishers and their marketing departments? Probably, and Paul Ewen is

right to point this out to me, though I am not sure that the Fancy Woman who

breeches Plug’s personal space, or the bankers who Plug chastises for swearing

in public would – as he tells them – ‘give a four-penny fuck’ (39) will “get it”.

Better to laugh the whole thing off as affectionate satire.

Comments

Post a Comment