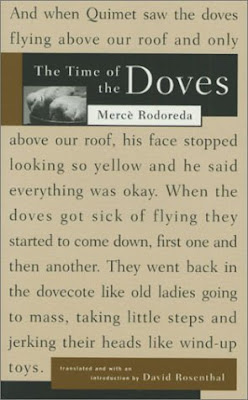

The Time of the Doves

According to the introduction (Graywolf Press edition, 1986)

Mercé Rodoreda started her career as a prolific writer with five novels by the age of about 28; by

1939 things changed dramatically. No only were Catalan books burned and Catalan

newspapers suppressed, but the author herself went into exile and felt

disconnected from her language and culture. In 1960, Rodereda returned to the

novel form and penned this stream of consciousness novel, in the voice of the

long-suffering Natalia from Barcelona. This is a life story which begins and

ends with courtship; of Natalia and Quimet, and much later with Natalia’s

daughter Rita and her love, Vincenḉ. This life cycle is interesting enough – on the basis of the close observations of domestic life and the

relationship between the married couple (with Quimet the domineering,

passionate kind – though not without interest in others). What makes it more

captivating is the way that the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath

enters the lives of the characters and changes their lives, seen from Natalia’s

point of view, far from any battle ground or city siege. We see the initial interruptions (charcoal

seller out of charcoal; milkman’s delivery ending; strikes and shortages).

Because Natalia has at this time a job cleaning the house of a more wealthy

family, we see the threat of the militia and there are stories of petty revenge

(while the wealthy family is portrayed not without criticism in terms of their

reported actions). Beyond this, churches are being burned and priests harassed

or worse, Quimet helps smuggle out of danger a local priest, while at the same

time joining the militia as a matter of immediate calling.

According to the introduction (Graywolf Press edition, 1986)

Mercé Rodoreda started her career as a prolific writer with five novels by the age of about 28; by

1939 things changed dramatically. No only were Catalan books burned and Catalan

newspapers suppressed, but the author herself went into exile and felt

disconnected from her language and culture. In 1960, Rodereda returned to the

novel form and penned this stream of consciousness novel, in the voice of the

long-suffering Natalia from Barcelona. This is a life story which begins and

ends with courtship; of Natalia and Quimet, and much later with Natalia’s

daughter Rita and her love, Vincenḉ. This life cycle is interesting enough – on the basis of the close observations of domestic life and the

relationship between the married couple (with Quimet the domineering,

passionate kind – though not without interest in others). What makes it more

captivating is the way that the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath

enters the lives of the characters and changes their lives, seen from Natalia’s

point of view, far from any battle ground or city siege. We see the initial interruptions (charcoal

seller out of charcoal; milkman’s delivery ending; strikes and shortages).

Because Natalia has at this time a job cleaning the house of a more wealthy

family, we see the threat of the militia and there are stories of petty revenge

(while the wealthy family is portrayed not without criticism in terms of their

reported actions). Beyond this, churches are being burned and priests harassed

or worse, Quimet helps smuggle out of danger a local priest, while at the same

time joining the militia as a matter of immediate calling.

The title comes from another passion of Quimet’s – that of doves.

He sets up a dovecote in the house and on the roof; Natalia is left to do most

of the work and comes to loathe the domination of the birds over her life. The

fate of the birds and her own intertwine, at least in terms of characterisation

and imagery: ‘And I took off. Higher, higher, Colometa … with my face like a

white blotch above the black of mourning …’ (p.151). There are several moments

of near madness for Natalia – such as a night when she walks the street with a

knife; otherwise she copes with the sort of fortitude and inner strength that drives

others to the extremes of faith or despair. This is an intimate portrait – not

of the Spanish Civil War directly – but exploring its profound effect of a good

woman’s life; a working-class woman who wants nothing more than safety, family,

and a little living. It helped me to understand something of the times through

this unique and yet very-relatable voice. It ends with ellipsis, which is not

to give anything a way but just to suggest the sort of novel it is – dealing

with moments mostly, but occasionally years …

Comments

Post a Comment