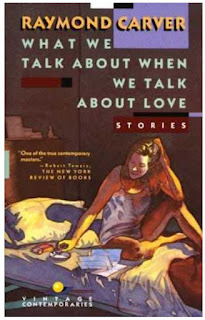

What we talk about when we talk about love

This is a very well known collection of perfectly written short stories by the American writer, Raymond Carver. They are best read with a glass of beer, or wine, or something stronger if you can keep your head. I am going to confess that this was my first Carver experience; I wouldn’t be original in saying that the economy of style reminds readers of Hemingway and that thematically the collection could also be placed alongside of Richard Ford’s short story writing (Rock Springs). So, we are talking about masculine prose, which manages to be both serious, sad, without "funny" irony, and yet also resonates in that human vein which American short story writers seem to manage better than anyone.

A

few examples of what’s in the collection – more for myself than for anyone who might

be kind enough to read this blog. ‘Why Don’t You Dance?’ is the opening story,

and it’s a story that speaks deeply through things that aren’t said (in that Hemingway notion of

the omisson). A man looks out the window at the front lawn where his furniture

lies, alongside his bed, a television, lampshade, and – for the story title –

his record player. A young couple pull up, assuming it’s a garage sale, and for

a moment lie on the bed as the man watches from inside. He comes out, serves

them whisky, puts on a record, sells things that they ask for at whatever price

they offer, and dances with the young girl. What’s unsaid, but painfully

present, is the man’s obvious ‘holding up’ in a crisis; a failed marriage; the

giving away of goods and meaning in a perverse ‘fu*% it’ attitude.

‘So

Much Water So Close to Home’ is almost as good as the Paul Kelly song. Yes,

that’s my attempt at irony. The story makes it’s meaning so intense by playing it

straight: a female narrator starts the story by saying simply: ‘My husband eats

with a good appetite.’ She judges her husband for what he has done – as the song tells

us, and as the excellent Australian film Jindabyne

dramatises – he's gone fishing with friends, found a body of a young woman, drowned –

and rather than return and ruin a fishing trip, camps and drinks for several

nights before reporting the tragedy.

Without giving the story away (it’s so

short) – ‘Popular Mechanics’ portrays a couple fighting over a child and ends

with one of those great lines in fiction, the sort Steinbeck or

Chekov would have approved of. Another story, ‘Tell the Women We’re Going’, portrays a life at

fast pace for two friends who live unfulfilled lives, and in the case of the more

seemingly settled of the two friends, repression of desires leads utimately to

cruelty, all the more powerful for its understated telling.

‘What

we talk about when we talk about love’ is a set of stories I am sure I will

re-read; they compliment an evening drink so well (Carver was an alcoholic and suffered

greatly as a result; so take this advice with due caution). The stories

resonate in the way all good short stories do – that economy of style, that theory

of omission, all those Hemingway-related cliches which just so happen to be

true in this case. Here’s the end of the ‘title track’ (it does in some strange way also

feel like an excellent LP); this gives you a sense of what’s at stake as a

drinking session goes on too long and too much is said, and yet not enough. Love between

friends and couples:

“I could hear my heart

beating. I could hear everyone’s heart. I could hear the human noise we sat there

making, not one of us moving, not even when the room went dark” (p.129).

Comments

Post a Comment