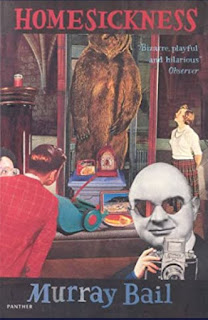

Homesickness

I have come to this novel rather late, having read Eucalyptus when it was released in 1998 and, I must admit, nothing by Murray Bail since (re-reading Eucalyptus to teach doesn’t really count). Homesickness was published in 1980, and I have found a second-hand, first paperback edition from that era. His other books are Holden’s Performance (1987); The Pages (2008) and The Voyage (2012). For a writer like me who churns out a novel every ten years, Bail’s pauses between novels are almost encouraging.

My main reason for reading this novel was to see how it

dealt with themes that might be said to connect with the expatriate experience.

I read that Bail lived overseas at the end of the 1960s in India, and then in

England and Europe from 1970 to 1974. Although Homesickness is a 1980 publication, it is most assuredly a 1970s

book; one can almost taste the stale Qantas food and touch the (probably)

too-proud wallpaper in Australia House in London, where two of the characters

do visit (and I am old enough to remember that strange place, where one entered

to read old Australian newspapers; Australia didn’t exist in British media then

– and probably doesn’t to this date and there was no internet umbilcal cord to the [other] mother country).

The short-story-like premise of this book is the rather unlikely

idea that thirteen Australians with no past-connections travel the world

together, and visit museums of the most outlandish mix of the banal and the

surreal. They begin in Africa, thence to London, to Ecuador, to New York, to

London again, and finally, too Russia. In Russia, there is an interlude where the

author shifts to first person and it seems, provides a minor autobiographical

note. Otherwise, the narrative utilises a shifting third person point of view,

and much, much dialogue (often amusing banter of the antipodean variety). Make

no mistake about it, Bail’s knowledge is encyclopaedic; and he is an absolute

craftsman at the sentence level. These traits make the scenes move along, even

as strange museum skits, such as an African museum which features our own

Robert Menzies; a discussion of English art galleries where photos of ‘French canals,

hay stacks and lily ponds’ have replaced the actual art (one assumes,

post-impressionist). There is a Yorkshire museum of corrugated iron, a New York

museum of marriage, and an Englishman whose nose can approximate the changing

colours of Ayers Rock (Uluru to you, mate).

And what of the expatriate experience I went searching for?

The characters are too many to know well, though the Italian-sounding Borelli

comes closest to our affection, with his wise thoughts amid much misunderstanding,

self-centred gazing, and wisecracks of the other characters. Here’s a few

quotations to get a sense of what I enjoyed – and you might, too – if you know

a good thing.

Isolation: ‘Australia? The word was not to be found [in

Britain], not even in the bloody shares page, Gary Atlas pointed out. It might

well not have existed’ (p.77)

Accent: ‘The Australian accent had remained. Words

unexpectedly flattened fell away in mid-air. But to Borelli they leapt out,

waving’ (p.100).

Australian egotism (a matador takes on Australian ‘toughness’):

‘Who are you? You have experienced, what, nothing … suffer through nature and

pain. Emerge strong’ (p.159).

Upside Down: ‘The heads of antipodeans glance upwards … with

its museums and plethora of laws and words the Centre of Gravity lies in the

Northern or Upper Hemisphere’ (p.185).

And there’s a great little collection of quotations in

literature and metaphors connected with kangaroos, just to remind this island

nation that our culture has travelled far, even as we announce it too loudly,

too proudly, as we might have particularly in the 1970s. A clever bunch of

homeless Australians – self-deprecating but sensitive when it all goes too

close to the bone (‘Aye, steady. What are you getting at?’ p.126).

Comments

Post a Comment