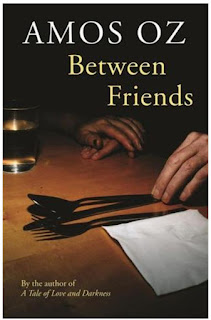

Between Friends

I bought the hardback of Amos Oz's Between Friends (2012) this year from a good bookstore, on sale for $5. I felt a bit sad buying the book at this price, like a man taking pity on a stray dog at the pound of some undoubtedly good pedigree, misplaced. And that feeling of melancholy lasted with me as I read the book, the fourth I have read by the Israeli writer, peacemaker, and intellectual. This is a short book so I will tell a little of my other readings first.

Black Box (1988) is written as a series of letters between divorcees with shared responsibility for their son, Boaz. Just having a character, Alec, as a university professor, travelling between locations as part of the correspondence introduces a political and social complexity. It’s an intellectual book about emotional issues; something that fills me with envy as a writer. In the Land of Oz (1983; 1993) is a memoir of voices of Israel and the West Bank from the 1980s – of both and all sides (if you can see that paradox) in the Arab-Israeli conflict; it’s something like a memoir, a travel story, and war correspondence that resonates with important reflections, like Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia. I read Panther in the Basement (1995) as semi-autobiographical, a twelve-year-old living in Jerusalem in 1947, with British soldiers on the streets and trouble at the door.

I understand that Oz is the author of some thirty books, so this is just scratching the surface. I do keep a line from Oz in my office at work, not because I can claim to be confronting anything like the difficulties Oz has thought about and lived through, but because as a teacher, I have opportunities to think about the notion of idealism and compromise in my own, small way. The quotation, from an interview reads as follows:

The concept

of compromise is not particularly in vogue, especially among young idealists.

This is because it is perceived as an immoral agreement; as a betrayal of pure

and absolute principles. For me, however, compromise is a synonym for life.

“Compromise” does not mean to surrender or to turn the other cheek, but to

succeed in meeting the other half way. The opposite of compromise is not

idealism, but fanaticism, which is equal to death.

http://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Regions-and-countries/Bulgaria/Amos-Oz-the- art-of-compromise-57191

It seems to me, that even if he wasn’t a great writer (and I think he is), Amos Oz would be worth listening to.

Between Friends can be read as either eight short stories, or as chapters in a novel that focuses on different characters or people living in a Kibbutz. The characters are all treated with great tenderness, even though they are clearly flawed people – flawed by idealism, in some cases, which can lead to an inability to compromise and let others grow. Flawed by the failure to live up to the high ethical standards demanded by a community that shares everything, including and especially gossip; flawed by youth and inexperience or age and bitterness. In ‘At Night’, Kibbutz secretary Yoav Carni, the Kibbutz’s ‘first baby’, is now a responsible if not particularly happy man. As he walks on the guard shift at night, he thinks: [he] didn’t believe in God, but in moments of solitude and silence such as this, Yoav felt that someone was waiting for him day and night, waiting silently and patiently, soundlessly and utterly still, and would wait for him always’ (p.116). Then he bumps into Nina, who has left her burly husband in the middle of the night in search of sanctuary – and Yoav is torn by a temptation to respond to signs of affection, while keeping faith with his detachment as a leader, and his own marriage vows. Oz utilises the symbolism of streetlamps to foreshadow the inevitable, when they are spotted talking together and whatever innocence there is in their conversation is bound to be misread. In another story, ‘Deir Ajloun’, a young man Yotam must confront the committee if he wishes to study abroad, something he doesn’t have the will to do – and yet escape he must. These are examples of the simple, human dilemmas which fill the stories, stories not based on immediate danger from the surroundings outside the Kibbutz, but from the sheltered life within.

A funeral ends the collection with the death of a holocaust survivor, an anarchist and a believer in ‘Esperanto’ (the title of the story). His eulogy could almost sound like the sort of tribute paid to Amos Oz: ‘He saw with his own eyes how low human beings could sink, but still came to us imbued with belief in people and in a future burning with the bright flame of justice’ (p.196). That’s not bad for $5, not bad for a short novel or collection of short stories, which allow the reader to listen to the ruminations of characters who think one thing, and often say something else. This is the nature of the simple yet profound resonance of the prose, as honest as any half-hidden, half-true conversations ‘between friends’.

Comments

Post a Comment